Advertisement

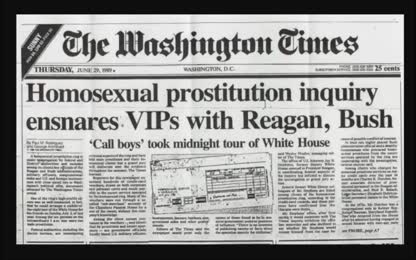

The Lightbulb Conspiracy aka Pyramids of Waste

2 Comments

Video Transcript:

tiene la idea o This is Marcos from Barcelona, but he could be anyone, anywhere. What is about to happen to him occurs daily in offices and homes all over the world. A part inside the printer has failed, and the manufacturer sends Marcos to technical support. My technical support is diagnostic, but it is a 5-hour-long day. It will be difficult to find the places to prepare it. It is not very good to prepare it, but to prepare it for about 100-100 euros. It has 39 euros. I would advise you to use new printers. So you will buy a new printer. If he agrees, Marcos will become yet another victim of planned obsolescence. The secret mechanism at the heart of our consumer society. Our role in life seems to be just to consume things with credit, borrow money to buy things with their needs. If a consumer does not purchase, the economy is not going to grow. The desire on the part of a consumer to own something a little newer, a little sooner than is necessary. This film will reveal how planned obsolescence has defined our lives ever since the 1920s, when manufacturers started shortening the lives of products to increase consumer demand. This characters are becoming sixteen or eight-year-old buyers that have set up industries. If we sell non-caயous meals to the consumer, we will get different behaviors, as it is used in the production of goods. First the consumer can buy the corresponding products which了 the output of principal assets — second the money prol整. The freedom of the consumer was kept a certain time. A new generation of consumers has started challenging manufacturers. Is it possible to imagine a viable economy without planned obsolescence, without its impact on the environment? Posterity will never forgive us. Posterity will certainly find out about the throw away lifestyles of people in the advanced countries. Welcome to Livermore, California, home of the longest burning light bulb in the world. My name is Lenoans and I am chairman of the Lightbulb Committee. It was in 1972 when we discovered that the light bulb that was hanging in the fire station was a significant light bulb. The light bulb at the Livermore fire station has been burning continuously since 1901. Ironically, the bulb has already outlasted two webcams. So very well, my own true love in the world. In 2001, when the bulb was 100 years old, the people of Livermore threw a big birthday party, American style. I think we were hoping if we would get 200 people would be happy and we ended up with 800 or 900 people showing up. One nation, 100 God, indivisible, indivisible, and indivisible. You think that anybody would sing happy birthday to a light bulb? Well, we didn't think they would, but they did. The Virgin of the Bold was produced in a town called Shelby, Ohio, back around 1895 and put together by some people. The Virgin of the Bold was produced in a town called Shelby, Ohio, back around 1895 and put together by some very interesting ladies that I have some pictures of and some gentlemen that invested in the company. The filament was invented by Adolf Schole. He invented his filament to last. Why does his filament last? I don't know. It's a secret that he made and that died with him. Schole's formula for a long-lasting filament is not the only mystery in the history of the light bulb. A much bigger secret is how the humble light bulb became the first victim of planned obsolescence. In 1924, a very special day was coming. In a winter room in Genf, some rivers were found in the nadal streams, to go into a secret plan. They founded the world-wide cartel, which is the goal of the global production of the entire country and the high-pitched world market to share it. This cartel had its name for bus. The goal was to control the production of the patent and to control the consumption. It's about the best for these companies when the consumer regularly buys the oil lamp and when the oil lamp is burning for a long time, it's an economic disadvantage. Initially, manufacturers strived for a long lifespan for their bulbs. The pandemic conditions were great, so I'm not saying. Thomas Edison's first commercial bulb, on sale by 1881, lasted 1,500 hours. By 1924, when the Phoebus cartel was founded, manufacturers proudly advertised lifespans of up to 2,500 hours and stressed the longevity of their bulbs. So, when the Phoebus was founded, we simply ordered the living power of these 11 bulbs at 1,000 hours. In 1925, the committee founded the 1,000-hour-life committee, which is based on technical basis, the living power of the bulbs on these bulbs. More than 80 years later, Helmut Houger, an historian from Berlin, uncovers proof of the committee's activities, hidden in the internal documents of the founding members of the cartel, such as Phillips in Holland, Osram in Germany, and company De Lohm in France. Here we have a cartel document that says, the average life of lamps for general lighting service must not be guaranteed, published or offered for another value than 1,000 hours. Under pressure from the cartel, member companies conducted experiments to create a more fragile bulb that would conform with the new 1,000-hour wall. The production was monitored rigorously to make sure cartel members complied. A large number of materials represent a proof standing in the middle of the sensor wave. All of those materials were carp depth, were perfectly detailed and looked to be retained. and films like Osram have then practically been being photographed for a long time. Davis enforced its rules through an elaborate bureaucracy. Members were fined heavily if their monthly life reports were off the mark. To Spain Here you have a strafthap 낶 puisque Tells how much it costs migrating from other countries. So it's industrial credit so much could lose up to 1500 hours. As planned, obsolescence took effect. Lifespans fell steadily. In just two years, they dropped from 2,500 hours to less than 1,500 hours. By the 1940s, the cartel had reached its goal. 1,000 hours had become the standard lifespan for bulbs. I can see how this was very tempting in 1932. I think at the time, sustainability was actually substantially less of an issue, because I don't think they looked at the planet as being one with finite amount of resources. They looked at it as from an abundance perspective. Ironically, the light bulb has always been a symbol for ideas and innovation, and yet it's one of the early and best examples of planned obsolescence. In the following decades, inventors filed dozens of patents for new light bulbs, including one lasting 100,000 hours. None of them reached the general market. Officially, the purpose of the film was to give up when the traces of the publicism were completely erased. The strategy behind it is to take it again in a certain time. Then it means that the international electricity cartel is again another name. It is decided that this idea of the institution is of course still exists. In Barcelona, Marcos hasn't followed the advice of the shopkeepers to replace his printer. He's determined to repair it, and has found somebody on the internet who was discovered what has actually happened to his printer. It's the dirty little secret of inkjet printers. I tried to print a document and it said parts inside your printer require replacement. So I decided to do a little servicing of my own. Hello, Marcos. I got your message. Marcos has contacted the author of the video. I looked into it and it turns out that there's a thing in the bottom of the printer called a waste ink reservoir. The way inkjet printers work is they constantly have to clean the print heads and they do that by squirting ink through them down a hole in the bottom of the printer into this great big sponge. There's just a preset time when it squirts a certain number of drops down there, then the printer decides it's full of ink and one function anymore. The justification is they don't want to put ink all over your desk. But I think the problem goes deeper than that. It's the way the technology works. It's just designed to fail. Planned obsolescence emerged at the same time as mass production and the consumer society. The whole issue with products being made to last less long is part of a whole pattern that began in the Industrial Revolution. When the new machines were producing goods so much more cheaply, which was a great thing for consumers, but consumers couldn't keep up with the machines. There was so much production. As early as 1928, an influential advertising magazine warned that an article that refuses to wear out is a tragedy of business. In fact, mass production made many goods widely available. Prices fell and many people started shopping for fun rather than need. The economy was booming. In 1929, the emerging consumer society came to a full stop when the Wall Street crashed sent the US into a deep economic recession. The unemployment reached staggering proportion. 1933, one fourth of our labor force was unemployed. People no longer queued for goods, but for work and for food. From New York came a radical proposal on how to kickstart the economy again. Bernard London, a prominent real estate broker, suggested ending the depression by making planned obsolescence compulsory by law. It was the first time the concept was put into writing. Under Bernard London's proposal, all products would be given a lease of life with a set expiry date, after which they would be considered legally dead. Consumers would turn them over to a government agency where they would be destroyed. He was trying to achieve a balance between capital and labor where there would always be a market for new goods. So there would always be a need for labor and there would always be a reward for capital. Bernard London believed that with compulsory planned obsolescence, the wheels of industry would keep turning and people would keep consuming and everyone would have a job. Giles Slade has come to New York to investigate the person behind the idea. He wants to find out if for Bernard London, planned obsolescence was purely about profits or about helping the unemployed. I have a picture of Bernard London. Dorothea Weitzner remembers meeting Bernard London in the 1930s during a family outing. Don't tell me which one he is. I'm not seeing. Oh, isn't that interesting? Yes. Definitely intellectual looking. You met Bernard London in 1933. When I was about 16, 17, my dad and mother had this big Cadillac car, which was the size of a zeppelin. The mother was driving like a chauffeur. Dad was in the front and Mr. Mrs. London were in the back of the big limousine. Dad said that Mr. London should explain his philosophy to me. He's a very interesting man. And he just told me in a few words that that was his idea to reduce the depression we were in an economic mess worse than today even. It was obsessed with this idea. Like an artist is the ugly obsessed with his paintings, you know? He actually whispered to me in the car afraid that his theory might be too radical. In fact, Bernard London's proposal was ignored. An obsolescence by legal obligation was never put into practice. Twenty years later, in the 1950s, the idea resurfaced, but with a crucial twist, instead of forcing planned obsolescence on the consumers, they were to be seduced by it. Plan obsolescence. The desire on the part of a consumer to own something, a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary. This is the voice of Brooks Stevens, the apostle of planned obsolescence in post-war America. This flamboyant industrial designer created everything from household appliances to cars and trains, always with planned obsolescence in mind. In the spirit of the times, Brooks Stevens designs conveyed speed and modernity. Even the house he lived in was unusual. This is the home that my father designed and that I grew up in. When it was being built out in the suburbs, everybody thought it was going to be the new Greyhound bus station because it did not look like a traditional home. One of the most important things that my father felt always in designing a product is that it made a statement. He detested products that were bland and really did not create any desire within the consumer to inspire the purchase. Unlike the European approach of the past where they tried to make the very best product and make it last forever, meaning you bought such a fine suit of clothes that you were married in it and then buried in it and never a chance to renew it, the approach in America is one of making the American consumer unhappy with the product that he has enjoyed the use of for a period. Haven't passed it on to the second hand market and obtain the newest product with the newest possible look. Brooks Stevens traveled all over the US to promote planned obsolescence in speech after speech. His approach became the gospel of the time. Women and men alike are increasingly interested in the look of things. They eagerly give their attention to what's new and beautiful and advanced. Design and marketing seduced consumers into always craving the latest model. My father never designed a product to intentionally fail or become obsolete for some functional reason in a short period of time. Expansion obsolescence is absolutely at the consumer's discretion. No one is forcing the consumer to go into the store and purchase a product. They go in under their own free will. That's their choice. Freedom and happiness through unlimited consumption. The American way of life in the 1950s became the foundation for the consumer society as we know it today. You see without planned obsolescence these places wouldn't exist. There wouldn't be any products. There wouldn't be any industry. There wouldn't be any designers, architects. There wouldn't be any salespeople, cleaners. There wouldn't be any security guards. All the jobs would go. So how often do you change your mobiles? These days planned obsolescence is an integral part of the curriculum at design and engineering schools. Boris Knuth lectures on the concept of product life cycle, a modern euphemism for planned obsolescence. Students are taught how to design for a business world dominated by one single goal, frequent repeat purchase. What I do, I pass these round and you tell me what you think, how long it takes for them to fail, what the service life will be. Designers have to understand what company they work for. The company decides on a business model how often do we want to renew our products, our offers. So this brief is given to designers and designers have to understand and design the product in a certain way so it fits exactly the business strategy of the client they work for. The planned obsolescence is at the root of the substantial economic growth that the Western world has experienced since the 1950s. Ever since, growth has been the holy grail of our economy. We live in a growing society, which is not to be satisfied with the needs but to grow, to grow to infinity, to grow without the limit of production and to justify this growth without the production, to grow without the limit of consumption. Serge Latush is a noted critic of the growth society and has written extensively about its mechanisms. There are three fundamental instruments that are the publicity, the obsolescence program and the credi. In the last generation or so, our role in life seems to be just to consume things with credit to borrow money to buy things we don't need. That makes no real sense to me at all. Critics of the growth society point out that it's unsustainable in the long run because it's based on a flagrant contradiction. The only thing that grows, that a growing infinity is compatible with a finite planet and whether a man or an economist. The drama is that we are all economists now. Why is it that a new product has created every three minutes somewhere in the world? Is this necessary? I think a lot of people have realized that things need to change when they're being told by politicians to go shopping or to start consuming as the best way to restart the economy. Looking at the service manuals of different printers, Marcos realizes that the lifespan of many printers is set by the engineers right from the start. They achieve this by placing a chip deep inside the printer. How do engineers feel about designing products to fit the printer? How do engineers feel about designing products to fail? The dilemmas captured in a British film from 1951 where a young chemist invents an everlasting thread. He believes that great progress has been made. But not everyone is happy with his discovery and soon he finds himself on the run, not only from the factory owners, but also from the workers, all fearing for their jobs. Well that's really interesting and it reminds me of something that actually happened in the textile industry. In 1940 the chemical giant DuPont announced the arrival of a revolutionary synthetic fiber nylon. Girls celebrated the new long lasting stockings that the joy was short lived. My father worked for DuPont before and after the war in the nylon division and he told me a story about how when nylon first came out and they were trying it out for use in stockings, the men in his division were asked to take these stockings home for their wise and girlfriends to try out. My father brought them home to my mother and she was delighted with the first products because they were so sturdy. The DuPont chemists had every reason to be proud of their achievement as even men touted the strength of nylon stockings. The problem was they lasted too long. The women were very happy with the fact that they didn't get runners in them. Unfortunately this meant that the companies producing the stockings were not going to sell very many. DuPont gave new instructions to Nichols Fox's father and his colleagues. For the men in his division it was back to the drawing board to try to make the fibers weaker and come out with something that was more fragile and would run so that the stockings wouldn't last as long. The same chemists who had applied their skills to make durable nylon went with the spirit of the times and made them more fragile. The everlasting thread disappeared from the factory floor just like in the cinema. We need control of this discovery. Complete control. If you want price to your money in that contract we will pay it. A quarter of a million. Just a press it. Yes. How did the chemists that DuPont feel about deliberately reducing the life of a product? It must have been frustrating for the engineers to have to use their skills to make an inferior product after they tried so hard to make a good product. But in a way I suppose that's the outsider's view. Probably they just had a job to do. Make it strong, make it weak, that was their job. Engineers were in a really complicated ethical time. This confrontation with planned-off solutions provoked them to examine their most basic ethical concepts. There was an old school of engineers who believed that they should make a permanent, usable product that would never break. And there was a new school of engineers that were driven by the market who were clearly interested in making the most disposable product that they could. And this debate resolved itself by these new school of engineers taking over. Planed-off solutions did not only affect engineers. The frustration of ordinary consumers is echoed in Arthur Miller's classic play, Death of a Salesman. Just like Willie Lomax, all consumers could do was complain powerlessly. Those that consumers know that on the other side of the Iron Curtain, in the countries of the Eastern Block, there was a whole economy without planned obsolescence. The Communist economy was not ruled by the free market, but centrally planned by the state. It was inefficient and plagued by a chronic shortage of resources. And such a system planned obsolescence did not make any sense. In former East Germany, the most efficient communist economy, official regulations stipulated that fridges and washing machines should work for 25 years. In 1981, a lighting factory in East Berlin launched a long-life ball. They took it to an international lighting fair, looking for buyers from the West. The Western buyers rejected the bulb. In 1989, the Berlin Wall came down. The factory was closed, and the East German long-life bulb went out of production. Now, it can only be found in exhibitions and museums. Twenty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, consumerism is as rampant in the East as it is in the West. But there is one difference. In the age of the Internet, consumers are ready to fight against planned obsolescence. The first movie we made that really broke through was a movie about the iPod. It was completely broke. I had gotten this iPod, it was like 500 bucks, 400 bucks. And about eight months later, 12 months later maybe, the battery died in it. And I called Apple to ask them to replace the battery. And their policy at the time was to tell their customers to buy a new iPod. It wasn't that the battery died that was annoying because in my Nokia cell phone, the battery dies, you buy a new battery. Even in my Apple laptop, when the battery would die, you replace the battery. But in the iPod, this expensive piece of hardware, when the battery died, you had to replace the entire unit. So my brother's idea to make a movie about just that. We went around with a stencil spray-paking and every iPod advertising we saw in town. iPods unreplaceable battery last only 18 months. We put the video on our own little site. iPods30secret.com. In the first month, six weeks, it was at 5, 6 million views. And the site went absolutely bananas. A lawyer in San Francisco, Elizabeth Pritzker, heard about the video and together with her associates, decided to sue Apple over the lifespan of the iPod battery. Half a century after the light bulb case, planned obsolescence was in court again. When we brought this litigation, this was two years after the iPod was introduced. Apple had sold about 3 million iPods nationwide in the United States. Many of the 3 million iPod owners were having battery problems and were willing to sue. One of them was Andrew Wesley. We selected from amongst the consumers who had called us, individuals who would serve as representatives in a class action. A class action is really a device that's fairly unique to the United States, where a small group of people stands in the shoes of a large group to bring one claim before a court. My role in that case was as class representative on behalf of thousands, maybe tens of thousands of people. The case came to be known as Wesley versus Apple. When my friends and family learned that this was a major case, they thought I was, you know, becoming a radical. You know, here I am, going to sue, you know, I was the next Aaron Brockovich. In December 2003, Elizabeth Pritzker filed the case at the San Mateo County Court, just a few blocks from the Apple headquarters. We asked Apple for a number of technical documents regarding the battery life in the iPod, and we received a lot of technical data about the battery design, about the testing of the battery, and learned through that discovery that the type of the lithium battery that was contained within this iPod was designed by design to really only have a short period of life. I do think that Apple's development of the iPod was intended to be a one-of-plant obsolescence. After a tense few months, both parties hammered out a settlement. Apple set up a replacement service for the batteries and extended the warranty to two years. The claimants were offered compensation. One thing that really bothers me personally is that Apple really promotes itself as a young hip forward thinking company, and for a company like that, not to have a good environmental policy that allows consumers to return products for proper recycling and disposal, really, is really counterintuitive and counter to their message. Planned obsolescence produces a constant stream of waste, which is shipped to third-world countries, such as Ghana in Africa. It's been between eight and nine years now when I noticed that loads and loads of containers were coming to this country with electronic waste. We're talking about the end of life computers, end of life television sets, which nobody wants in the developed countries. Shipping electronic waste to third-world countries is forbidden by international law, but the merchants use a simple trick. They declare the waste as second-hand goods. More than 80% of the electronic waste that arrives in Ghana is totally beyond repair, and whole container loads are abandoned at dump sites all around the country. We are at the dump site here in Aguibloshi. In the past, we had this beautiful river called Odoar River, that meandered its way through this area. It was teeming in the past. It had so much fish. We actually attended the school, not very far away from here, so it would come play football and hunger around the river. The fishermen would organize boat rides, I remember very well, but now it's all finished, it's all gone. And that makes me really, really sad, and it makes me hungry. These days, there are no school kids playing here after class. Instead, youngsters from poor families come here looking for scrap metal. They burn the plastic covered cables from the discarded computers to salvage the metal inside. What is left is picked through by the younger children who are looking for any tiny pieces of metal, which the older boys may have missed. Some of those behind the shipments have said that, well, we're trying to bridge the digital divide between Europe, America, and then the rest of Africa and Ghana or course. But the reality is that these computers that are sent here simply do not wake. There's no point in receiving an electronic wish when you cannot deal with it, more so when you did not produce it, and your country is being used as a world's trash bin. The trash that's for so long in an industrial age has been hidden from view is now coming into our lives and we can actually no longer, reasonably avoid it. The waste economy is reaching its last legs because there's no physically have anywhere else to put the waste. I think in the course of time, we've come to realize that the planet that we're living on cannot sustain that forever. There's a limit to natural resources and there's a limit to energy resources that we have. Posterity will never forgive us. Posterity will certainly find out about the throw away attitudes, the throw away lifestyles of people in the advanced countries. People all over the world have started acting against planned obsolescence. Mike Anani is fighting against it from the receiving end. He has started by collecting information. This is where I keep the e-wist that have asset tags or property tags. This says Armu Center not West Jailand. It's from Denmark. This is from Germany sent here simply to be done. It was Minsda College. Apple, Apple she know better. It's a company that claims to be so green. There's a lot of Apple products that have been dumped here. I have a database that contain the asset tags, the contact addresses, telephone numbers of the companies that owned the electronic wizard have been dumped in Ghana. Mike Anani plans to turn this information into evidence for a court case. We need to take some action, some punitive measure. We need to see people so they stop dumping e-wist in Ghana. Marcos is on the internet again looking for a way to extend the life of his printer. He has discovered a Russian website which offers a free software for printers with a counter chip. The programmer has even gone to the trouble of explaining his personal motivation. This happens due to bad construction. This is where business model. Not a good one for user and environment. So I looked and found a way to make user-friendly software to allow active users resident in bad counter. Marcos doesn't know what to expect but downloads the software anyway. From a small village in France, John Thackera fights plant obsolescence by helping people share business and design ideas, ideas which come from all over the globe. In all poorer countries, things are repaired automatically. The notion you throw a product away just because it breaks for some reason is completely unknowable and unthinkable actually to somebody in the south. In India, there's an actual word, you guard to describe this tradition of being able to fix things pretty much regardless of the complexity of it. We try to find people who are actively doing projects in the world rather than just talking about things or making abstract statements about how awful things are or what has to be changed. One of these people is Warner Phillips, descendant of the dynasty of libel manufacturers. I remember my grandfather taking me to one of the Phillips factories in Einthoven to show me how libels were mass manufactured in factories. This is very, very cool. Nearly a hundred years after the creation of the light bulb cartel, Warner Phillips follows family tradition with a different approach. He produces an LED bulb which lasts 25 years. It's not like there's a green world and there is a business world. I think business and sustainability go hand in hand is actually the best basis to build a business and the only really real way to do that I believe is to factor in the true cost of the resources that have been used but you also look at the energy consumption, you also look at the indirect energy consumption of transportation. If we really did pay the co-real of the transportation, we would say that the petrol is a resource that is not renewable and for which we don't really have a substitute, I would say that transportation should be multiplied by 20 or 30. If you factor all of that in into every product that you manufacture, then there will be huge incentives for manufacturers and entrepreneurs all over the planet to make products at last forever. Fighting against planned obsolescence can also be achieved by rethinking the engineering and production of consumer goods. A new concept called cradle to cradle claims that if factories work like nature, planned obsolescence itself would become obsolete. Nature produces abundantly but fallen blossoms, dead leaves and other discarded materials are not waste. They become nutrients for other organisms, a cycle. Browngard believes that industry can imitate this virtuous cycle of nature. He proved that this is possible when he redesigned the production process of a Swiss textile company. Browngard found that hundreds of highly toxic dyes and chemicals were routinely used at the factory. For the production of the new fabrics, Browngard and his team reduced the list to 36 substances, all biodegradable. For the more radical critics of planned obsolescence, reforming production is not enough. They want us to rethink our entire economic system and our values. This revolution is called decroof. Serge Latush travels from conference to conference explaining how to get out of the growth society altogether. The production process of decroissance is able to reduce our ecological footprint, reduce our gaspillage, our production and our consumption. Reduising the consumption, reducing the production, but in the free time of the book, we can develop other forms of wealth that we can prevent from being and not being able to control consumption as the friendship, knowledge. We increasingly rely on objects to give us a sense of self-esteem and identity. Partly, the consequence of the breakdown of things that used to give us identity-like membership of a community or relationship to the land or all sorts of soft and social things, which have been replaced by consumerism. If the happiness depended on the consumption level, we should be in absolute happiness because we consume 26 times more than in the time of Marx. But all the conquests that people are not 20 times more happy, because happiness is always something subjective, obviously. Critics of decroof fear that it will destroy the modern economy and take us straight back to the Stone Age. The world is quite big to satisfy all needs, but it will always be too small to satisfy the speed of a few years. Marcos is installing the Russian freeware on his computer. The new software allows him to reset the counterchip inside his printer back to zero. The printer immediately unblocks. The computer has been rijped, precisely to von John Valde, who grants arrives to Lなので No editing also revolt. The internetünkü world is one of the main features of this software which is active organisations and Unityран FOR60 Eddy stream over exciting city� with different Creaks and territories in particular than the one of which that triggers problems if the skin bald testing is Collaborated in Stockholm and Kont at 1pm if only then I do not know about this point As I still don't know about the screen, unfortunately we're asked about the subargDE ke. and therefore I Ballay

Donate

Donate